Three Schools Of Thought: Confucianism, Existential Thoughts Of Socrates, Buddha And Lao-Zhu, And The Monotheism Such As Christianity And Islam) Vs. Φιλοσοφία (Philosophia,”Love of Thinking”)

193.Three Schools Of Thought That Have Impacted Humans Up To The Present

Three Schools Of Thought: Confucianism, Existential Thoughts Of Socrates, Buddha And Lao-Zhu, And The Monotheism Such As Christianity And Islam) Vs. Φιλοσοφία (Philosophia,”Love of Thinking”)

translated by Kyoko Saegusa

I do not like monotheism, which purports that, “There is only one god,” “God exists,” “the voice of God, “ “Be obedient to God,” and so on. I think monotheism is a troublesome idea.

Ito Hirobumi and other radicals at the time of Meiji Restoration came up with the kind of pseudo-monotheism (the Emperor as a “living god”), which is a copy of the transcendental deity worship I have described above. I consider this line of thinking absurd and dangerous. At least, it is definitely strange when one tries to measure it by modern common sense.

There is no question that the basic mission of contemporary education is to make sure the learner won’t develop such a strange state of mind, a mindset that is akin to being possessed. Education must help the learner develop vibrant, free and healthy spirit, and the ability to make sound judgment on her/his own.

------------------------------------------

There are three schools of thought that have influenced humans to this day. Let us have an overview of each school.

The earliest school that appears in history is of Confucius’ from 6th Century B.C. His thought was developed into Confucianism, which in turn led to the formulation of Cheng–Zhu school and Yangmingism. Yangmingism puts an emphasis on practice and action, and it can work positively or negatively. In recent times it was the supporting ideology for Mishima Yukio, who formed Tate no Kai (Shield Society) and subsequently committed seppuku on the premise of the Ichigaya Camp, the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

Originally, Confucius’ ideal was monarchy, which was already a disintegrated system in his time. He thought monarchy ought to be brought back, and he developed the morality and way of life and thinking for those who were to serve the monarch. His thoughts were compiled into what is known as the Analects. It does contain some wisdom and words of universal goodness, but all in all it shows how to serve those who are above you. Mito School of Thought, which supported the royalism (honoring the lord, the Emperor as a living god) also bases its principles on Confucianism. Its principles are based on feudal ethics that strongly advocates the hierarchical mindset, and it does not fit a democratic society that “acknowledges mutual freedom based on the equality of human existence.”

Nevertheless, Confucianism still has power over us even now. It is because democratization is slow developing in places such as workplaces and school athletic clubs; feudalistic or totalitarian managerial structures have a strong grip on their members. Japanese culture lacks in substance; it is characterized with just two words: form and ranking. It is because of this deeply rooted negative heritage of Confucianism as religion and as a school of thought

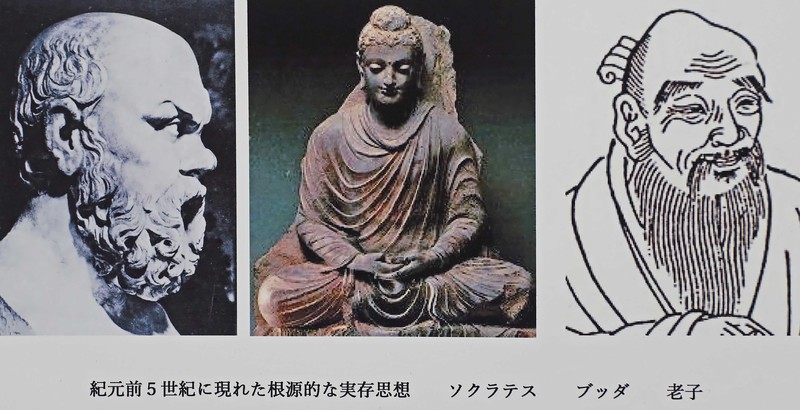

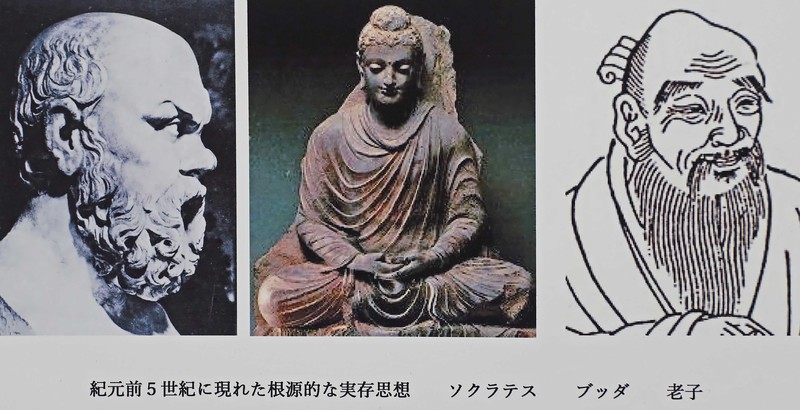

The next thought to appear 80 years after Confucius was existential thoughts, which was developed in succession in 3 places in the world. The thinkers were Socrates, born in 469 B.C. in Athens in the coast of the Aegean sea; Buddha (463 B.C., according to Dr. Nakamura Gen) in India (Nepal), and Lao Zhu (? c.320 B.C.) of China. I will not go into detail here but all three thinkers advocated that how one lived must be determined by the person from the heart and truthfully, not for the convenience of the nation or the totality (to benefit the ruler).

To Socrates the idea of absoluteness or strict prohibition did not come into consideration. He strived to reach universally acceptable (to the self and others alike) way of thinking through διαλεκτική(dialectics), which uses one’s own mental capacity and dialogue to reach superior thoughts.

Buddha (Śākyamuni) said that for every human being there was “only oneself, and this oneself is precious as is.” He made it clear that the truth was that everything happened as a consequence of Nidana (cause, motivation or occasion), and he reached the fundamental idea that one could ultimately only rely on oneself and that was the law (dhammasarano, relying on self, relying on dhamma/dharma). His teachings are filled with benevolence.

Socrates’ thoughts and those of Buddha’s have affinity with each other, and their basic thought overlaps. This must be because both schools of thought are founded on the mixing and blending of Arian and indigenous thoughts and people. The two were born only a few years apart. After they died, Greek kings and Buddhists had vigorous exchanges in the 3rd century B.C., and many Greek kings became Buddhist. There were meaningful dialogues between the two groups. Neither group had the notion of transcendental god(s), and they trusted humans’ ability to think reflectively when they dialogued, creating concertos of wisdom, as it were.

The key concept of Lao Zhu of China was, “Don’t try, just be.” He criticized Confucianism, and developed profound thoughts of ecology and feminism that would destroy discriminatory and dictatorial human relationship and bring about peace through the feminine principles. These three thinkers advocated thoughts that deeply acknowledged and cherished the humanity of each and every individual. Their thoughts can be said to be the most fundamental existential thoughts.

Lastly, there appeared the Christ (son of God) who preached the conversion to the only god, and Muhammad, his younger brother in status who was “the one who delivered God’s teachings.” These two brother religions were borne out of Judaism, the national religion of the Jewish people. Christian faith was born as a reformation of Judaism, and its younger brother is Islam. The intensity of the hatred between the two close brothers is widely known in the history of the long and horrendous religious warfare called the Crusade.

It is apparent that the idea of obeying and worshipping the absolute god (the Creator) and the existential thoughts I have described above are fundamentally incompatible with each other. Christian churches rehashed Greek philosophy and created an enormous system of theology called Scholasticism. The reformation of it is the modern Western European philosophy starting with Descartes in the 17th century. Japan directly imported West European scholarship in the Meiji Era, and when we say “tetsu-gaku” (philosophy) in Japan it refers to this school of thought. This view of thoughts is only one facet of thinking. Philosophy as Descartes conceived was the reformation of the previously existed theology, although he mentions the proof of the existence of God in the second chapter of his seminal work, Discourse on the Method.

Modern Western European philosophy is in essence the system of logic that is secularized Christian faith. It therefore inherits the purpose of Scholasticism – to understand the existence of humanity and its world in a comprehensive way. Thus, their logic is doomed to become complicated and hard to understand, to become a system of logic that is a structure made up with words. This reached its peak in the German idealism that peaked with Kant and Hegel.

It would be an impossible feat to comprehend and explain human existence and the totality of the world in a comprehensive way, unless one resorts to the religious oracle or something. One may say that West European “modern philosophy” was an attempt to achieve such an impossible feat. One can say that its history ended in 1966 with the dialog between Heidegger, who is said to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, and Spiegel.

In the dialog with Spiegel, Heidegger maintained that we could no longer expect anything from philosophy, that cybernetics would occupy the place of the conventional philosophy, and that various branches of science would replace philosophy. He repeatedly said that philosophy was powerless, that the only thing the humankind could do would be to wait for something like “god” in a few hundred years. This meant the failure of Heidegger’s ontology (the total understanding of the humans and the world). We may say that this was his “declaration of the defeat of philosophy.”

In his late years Heidegger decamped from West European philosophy and became an ardent follower of the thoughts of Japan’s Shinran.

It can be said that the history of West European modern philosophy began in the 17th century and ended in the 20th century. This philosophy had Christian monotheism as its backbone and began as yearning for the ancient Aegean civilization, as seen in the Renaissance movement. They rehashed Greek philosophy (Φιλοσοφ?α, Philosophia,”love of thinking”) into Christian theology, and built their philosophy upon it. It inevitably was built on quite a contrived structure of thought (metaphysics).

。

------------------------------------

The Φιλοσοφία, (philosophia,”love of thinking”) that I advocate activates feelings and thoughts in individuals so that people can strive for meaningful life. In everyone’s heart there is innate yearning for goodness, beauty and the pursuit of truth. The way of life I advocate has this “love of thinking” as its unmovable coordinate axis. Thus, it shares the fundamental principle with the 2nd of the 3 schools of thought mentioned above. It supports our day-to-day existence with the attitude, “He that would know what shall be must consider what has been,”which Socrates, Buddha and Lau Zhu taught us. It is a principle that is open and looks to the future.

Buddhism in Japan shares the same foundation of thought as “love of thinking”, but the nuance differs greatly between the two.

“Love of thinking” comes from a line of thinking that is realistic, proactive, open and cheerful. At its base is the attitude to learn from the goodness that children possess. It is the realization of neoteny, a characteristic humans possess.

One significant difference between the two ways of thinking is their understanding of sex. “Love of thinking” looks upon love as a symbol of humanistic life and approves it as something positive, as Plato has Socrates describe it in Symposium and Phaedrus.

Socrates considers the passion for romantic love, including Eros, the sexual love, as the source energy for one’s pursuit of goodness, beauty and truth. “Love of thinking” also respects the naturalness of humans, and sincerity and seriousness are not something stifling but are equally valuable as the pursuit of love. Furthermore, Lao Zhu’s principles are ultimately feminine principles, which deem the bondage between a woman and a man through sexual love as an expression of human sincerity. Lao Zhu says that the energy from such bondage spreads to one’s homeland and the nation, and eventually turns into compassion (philanthropy, virtue).

I will next concisely describe “love of thinking” and publicness.

The existential thought of “love of thinking” is an idea presented as “subjective knowledge” which supports public philosophy (Correspondence between Kim Tae-chang and Takeda). “Love of thinking” possesses publicness that is open to society. It decisively says No to the kind of politics and nationalism that are imposed by specific social classes. It ultimately is all about the autonomy of the citizens for the citizens by the citizens, that is, democracy. It strongly seeks peace and opposes any use of weaponry and warfare unless there is a direct attack to it.

It rejects the hierarchized view of humans based on the differences that are attached to people at birth, and fully embraces the ethics of sharing. These values are shared in Buddha’s thoughts. It does not value the amount of “possession” of knowledge, background, or wealth. It sees values in the goodness and attractiveness that lie in “the existence of the person oneself.” It rejects comparison and competition with others and holds thorough understanding of others as the basic principle. It embodies the kind of thinking that enables everybody to be able to display her or his own brilliance and charm. In order to realize such manner of thinking and attitude, it seeks the liberal economic system based on the laws and structure that do not create disparity.

I by no means deny the thoughts and life style of religious persons, but I believe that the only thing we can show our children is existential thoughts. Teaching children to believe in monotheism, or to obey the kind of moral that tells them to serve who is above them in rank, is unquestionably a “forbidden move.” My 40 years of educational practice is based on the existential thoughts described above. Such thoughts are one and the same as abundant love that is expressed with the whole body and mind.

Photos counter-clockwise:

1979- Gathering to view celestial bodies via the telescope

2008 Debate at the Hose of Senate (55 years old)

2014 Tenth anniversary celebration of the completion of New Shirakaba Education Hall

2015 The 40th Shikinejima Island Camp Diving (63 years old)

In Chapter 2 of Φιλοσοφία(Philosophia,”love of thinking”) I described the “healthy approach to life,” which is based neither on monotheism nor on secularism.

In Chapter 2 of Φιλοσοφία (philosophia,”love of thinking”) I explained the basics of the life and thought of humans. I pointed out that the conventional philosophy of Western Europe and social thoughts are under the influence of Christian Faith, that we must examine the way we have studied such thoughts and what kind of life one leads under such thoughts. I also wrote that we must find a new approach to understanding such thoughts.

https://www.shirakaba.gr.jp/home/tayori/k_tayori150.htm

The tool for understanding such thoughts is Φιλοσοφία(philosophia,”love of thinking”). It is not religion. It is a broadly defined philosophy. Without it we are not able to examine any domain (be it a religion or some kind of –ism) that is related to thoughts without hindrance and with confidence.

In post-Meiji Japan in particular we directly imported scholarly studies of Europe and America. Such studies were strongly influenced by Christian Faith. As a consequence Japanese scholars are prone to be sympathetic toward the Christian way of understanding without even realizing. This results in heavily biased view of humans and society. To rectify the bias the foundation of human life must be clearly and precisely explained without the notion of monotheism.

Again, Φιλοσοφία(philosophia,”love of thinking”) is broadly based philosophy, and serves as the basis for such scrutiny. It is of utmost importance that we make sure the transcendental “truth” outside of us does not come into the picture, and that people must be convinced with clear awareness that there is no other way to live but adopt the practice of feeling and thinking with one’s own mind and body as the coordinate axis. Any essential progress is impossible without the “internally motivated living” based on this way of living from day to day. It is not possible to take a critical look and scrutinize conventional thoughts without it.

This idea of Φιλοσοφία(philosophia,”love of thinking”) is not a system of logic. Nor is it of religious nature. It is about one’s attitude that makes it possible to bring about good results in various realms through living well from day to day. It really works deep inside without the person even realizing. “Love of thinking” is a principle that enables free and resilient living without strong religion (such as Christian Faith or the worship of Japanese emperor) or strong ideology (such as Marxism).

“Love of thinking” shares the fundamental principles with the existential thinking of Socrates (Athens) and Buddha (Nepal/India) in the 5th century B.C., followed by Lao Zhu (China), and also Shinran in Medieval Japan, and Sartre (France) in the 20th century. It is a thought that brings the blooming of humanness in us.

Takeda Yasuhiro, October, 2018. (66 years old)

At the athletic meeting with his grandchildren, Nana & Ren.

The girl on my back – I don’t know who she is. (Laugh).

About Philosophy and Love of Thinking – The Translator’s Perspective

Kyoko Saegusa

Φιλοσοφία(philosophia) is usually translated as philosophy, with an annotation “love of wisdom” in English. It looks straightforward, and most English readers do not have to think further. The word philosophy has several definitions in contemporary English dictionaries, from “the study of the fundamental nature of knowledge, reality, and existence” to “a guiding principle for behavior”. (The New American Oxford Dictionary)

The English word philosophy was introduced into Japan in the mid 19th century and the back translation of the Japanese word 哲学(tetsu-gaku) means something like “the study of thoughts, wisdom, reason.” It does not suggest in any way that the etymology is “love of wisdom.”

In the English translation of this thesis, the author and translator have decided to adopt the somewhat awkward English rendition “love of thinking” for Φιλοσοφία (philosophia). This is to make it clear that the author is not talking about philosophy in the sense of the academic discipline but in the original sense of loving to figure out life, wisdom and truth through thinking and knowing.

人類思想の三分類と恋知

「儒教・儒学」、「ソクラテス・ブッダ・老子の実存思想」、

「キリスト教・イスラム教などの一神教」 と 「恋知」

わたしは、神は唯一なり、神は実在する、神の声、神に従う、などという一神教は、嫌いというより、困った思想であると思っています。

その絶対神=超越神を真似て「疑似一神教」(天皇現人神)をつくった伊藤博文らの明治維新の過激な人たちの思想は、愚かで危険だと見ています。少なくとも近代社会の常識から見れば、異様な思想であることは明白です。

こういう異様な心=何かに憑りつかれた精神に陥ることのないように注意し、生き生きと自由で健康な精神=自己判断能力を育てようとするのが、現代の教育の基本的な使命であることは間違いありません。

--------------------------------------

では、現代にまで影響を与えている人類の三つの思想について概観してみましょう。

歴史的に一番古いのは、紀元前6世紀に現れた孔子です、それは儒学となり、その流れは、朱子学や陽明学を生みました。陽明学の実践・行動重視の考え方は、+にも-にも働き、最近では盾の会をつくり市ヶ谷自衛隊駐屯地で割腹自殺した三島由紀夫を支えました。

元々、孔子は、当時すでに崩れていた「君主政治」を理想と考えていました。君主政治に戻すべきと考えていた孔子は、君子が踏まえるべき道徳を示しましたが、孔子の死後は民も踏まえるべき考え方・生き方とされ、『論語』として知られます。それは、含蓄に富む言葉や普遍的なよきものに通じる思想も持ちますが、全体としては、上位者に仕える人間の生き方を示しています。孔子の思想は、権力と財力をもつ君子の側の道徳でしたが、持たざる者の道徳ともされた為に、被支配者が耐え忍ぶという逆転が生じたわけです。日本の明治維新の尊王思想(天皇現人神)を支えた水戸学も儒学です。上下意識に基づく道徳であり《人間存在の対等性に基づき互いの自由を認め合う》という民主主義の社会には適合しません。

しかし、いまなお力をもつのは、会社や学校や運動部などで民主化が遅れていて、古い全体主義的な組織運営が根強く残っているからです。日本文化が内容に乏しく「形と序列」の二文字で収まるのも、儒教・儒学の深い負の遺産と言えましょう。

次には、孔子に遅れること80年、世界の三か所で連続して誕生したのが「実存思想」です。紀元前5世紀にエーゲ海沿岸のアテネに生まれたソクラテス(BC469年)と、インド(ネパール)に生まれたブッダ=釈迦(BC463年中村元説)と、中国にうまれた老子(BC320年頃)。ここで詳しく説明はできませんが、異なる点はあっても、みな、人はどのように生きるか、を国家とか全体の都合で考えるのではなく、一人ひとりの心の真実から立ち上げた思想として重なります。

絶対とか厳禁という考え方とは無縁で、誰かに従うのではなく、各自の思考力と対話により優れた考えを導くというディアレクティケー(問答法)により普遍的(自他ともに深く納得できる)考え方を目がけたのがソクラテスです。

人はみな唯我独尊として生まれてきたというブッダ(釈迦)は、すべては縁により起こるという真実を明らかにし、究極の拠り所は自分であり法則である(自帰依ー法帰依)という根本思想につき、慈悲に満ちています。

ソクラテスの思想とブッダの思想は、親近性をもち、基本思想が重なります。それは、両者ともアーリア人と現地人との混合・混血の上に成立しているという事情によるのでしょう。生年も数年しか違いません。両者の死後、紀元前3世紀にはギリシャ王たちと仏教者とは盛んに交流をもち、多くのギリシャ王が仏教に帰依していますし、内容豊かな対話も残されています。超越的な「神」という概念を持たず、人間の思索の力を信頼して対話をする両者は、知恵の協奏といえます。

中国の老子は、無為自然をkeywordに、儒学を批判して差別や権力的な人間関係を大元から断ち、女性原理につくことで平和をつくるエコロジーとフェミニズムの深い思想を展開しました。これら三者は、みな、異なる一人ひとりの人間性を深く肯定し愛する思想で、もっとも根源的な【実存思想】と言えます。

最後は、唯一神への帰依を説くキリスト(神の子)であり、その弟分として生まれたムハンマド(神の教えを伝える者)です。この二つの世界的な兄弟宗教は、ユダヤ民族の国家宗教である「ユダヤ教」から生まれたものです。ユダヤ教の宗教改革として生まれたのがキリスト教であり、その弟分がイスラム教です。この二者の近親憎悪の激しさは、戦い(殺戮・略奪)の歴史=十字軍の長く凄まじい宗教戦争として有名です。

言うまでもなく、絶対神(創造神)に従い信仰するという思想と、上記の実存思想とは、根本的に異なる考え方です。

キリスト教会は、ギリシャ哲学を換骨奪胎することで膨大な神学体系をつくりました。スコラ哲学と呼ばれますが、その改革として出てきたのが17世紀のデカルトに始まる近代西ヨーロッパ哲学です。西欧の学問を明治に直輸入した日本では、哲学といえば、この思想を指しますが、それでは一面的な思想の見方になります。神学の改革としての哲学と言えども、デカルトは代表作の「方法序説」の二部では、神の存在証明を書いているのです。

近代西欧哲学は、本質的にキリスト教の世俗化としての理論体系ですので、スコラ哲学がめがけたもの=人間存在と世界の全体をトータルに解明し叙述しようとする意思を受け継いでいます。そのために、理論は複雑で難解となる宿命をもち、言葉の構築物としての論理の体系となり、カントからへーゲルに至るドイツ観念論でピークに達しました。人間存在と世界の全体をトータルに解明し叙述するというのは、宗教の宣託のようなものでない限り出来えない不可能事ですが、その出来えないことの努力を続けたのが西欧の「近代哲学」だとも言えます。その歴史は、20世紀最大の哲学者といわれたハイデガーが1966年に行ったシュピーゲル対話で幕を閉じたと言えるでしょう。

シュピーゲル対話では、ハイデガーは、哲学にはもはや何も期待できないと言い、従来の哲学の地位はサイバネティクスが占め、諸科学が哲学の替わりをする、と主張しました。哲学は無力だと繰り返し述べ、われわれ人類にできることは、何百年後かに現れる「神」のようなものを待つだけだ、と言いましたが、これは、ハイデガーの存在論(人間と世界のトータルな解明)の挫折であり、「哲学の敗北宣言」と言えます。

晩年、西欧哲学から離れた彼は、日本の親鸞思想に心酔しました。

17世紀に始まり20世紀に終わったのが西欧近代哲学と言えますが、この西欧哲学(キリスト教という一神教がバックボーンにある)は、ルネサンスの運動で明らかなように、古代エーゲ海文明への憧れに端を発していて、ギリシャのフィロソフィー(恋知)を換骨奪胎してキリスト教神学をつくり、その上に乗ったものでしたから、相当な無理の上に建てられた思想(形而上学)の建造物であったわけです。

--------------------------------------

わたしの提唱する《恋知》とは、一人ひとりの感じ・想い・考える営みを活発にすることで、意味充実の生を目がけるものです。誰の心にも先天的に備わっている善美へ憧れ心と真実を知りたいという心を不動の座標軸とする生き方ですので、二番目の実存思想と重なります。ソクラテスやブッダや老子に学ぶ温故知新の営みで、日々を支え、未来へ向けて開かれた考え方ー生き方の原理です。

わが国の宗教である仏教と「恋知」は思想の土台は同じなのですが、ただし、色合いはかなり異なります。

「恋知」という発想は、現実的で能動性が強く、開放的で明るいのです。子どものよさに学ぼうとする発想がいつも元にあります。いわゆるネオテニーという人間の特性の顕在化です。

また、とても重要な違いは、性に対する考え方です。「恋知」は、ソクラテスの思想(「饗宴」「パイドロス」)と同じで、恋愛を人間の人間的な生の象徴として捉え、よきものとして肯定します。ソクラテスは、エロ―スという性愛を含む恋愛への情熱を、善美や真実を求める動力源と考えますが、「恋知」も同じく、人間の自然性を尊び、真剣や真面目も、堅苦しいものとしてではなく、それらを、恋愛における態度と同じものとします。更には、老子の思想は女性原理につき、性愛による女男の結びつきを人間の誠(まこと)とします。そのエネルギーが郷里、邦(国)へと広がり、「慈」(博愛・徳)になるとするのです。

次に「恋知」と公共性について簡潔に記します。

恋知という実存思想は、公共哲学を支える「主観性の知」として提示されている通り(金泰昌と武田康弘の哲学往復書簡)、公共性をもち社会に向けて開かれていて、特定の階層による政治や国家主義に対して、明確に否と言い、市民の市民のための市民による自治政治=民主性・民主政・民主制につきます。平和への希求を強くもち、直接攻撃を受けたのではない限りは、あらゆる武器使用と戦争に反対します。

人間の生まれによる上下意識も元から排し、分かち合いという倫理につきますが、これらは、ブッダの思想と重なります。知識や履歴や財産の【所有】の多さに価値を置かず、【存在】そのもののよさ=魅力に価値を見ます。他との比較・競争主義を排し、納得を原理として、誰もがそれぞれの輝き=魅力を発揮できるような思想の態度です。その実現のために、格差を生まない法と制度に基づく自由主義経済を求めます。

わたしは、もちろん、宗教者の考え方ー生き方を否定はしませんが、こどもたちに示すことができるのは、「実存思想」しかないと思っています。一神教を信じることを教えたり、上位者に仕える道徳を守れ、と教えることが「禁じ手」であるのは自明でしょう。わたしの40年以上にわたる教育実践は、上記の実存思想に基づいたもので、それは、心身全体による豊かな愛情と一体です。

恋知 第2章では、一神教ではなく、世俗主義でもない「健康な生き方」を提示しました。

わたしは、恋知2章で、人間の人間としての生き方・考え方の基本を書きました。その土台の提示と共にキリスト教の影響下にある従来の西ヨーロッパ哲学や社会思想への見方、学習の仕方や生活仕方などについての反省と新たな考え方を記しました。

それは、宗教とは異なる「恋知」という広義のフィロソフィーですが、それなくしては、囚われなく自信をもって思想に関連する領域(宗教であれ主義であれ)を検討することはできません。

とりわけキリスト教の強い影響下にある欧米の学問を直輸入した明治以降の日本では、学問に携わる人は、知らぬ間にキリスト教シンパに陥りがちですので、人間や社会の見方には大きな偏りが生じます。その歪みを正すには、一神教(唯一神)によらずに人間の人間的な生の土台が説得力をもって明瞭・分明にされる必要があります。

恋知という広義のフィロソフィーは、そのための基盤です。外部に超越的な「真理」を置かず、自分の心身と頭で感じ・想い・考える営みを座標軸とする生き方以外はないことの明晰な自覚は、何よりも大切です。その考え方に基づき日々を生きる「内発的な生」なしには、何事でも本質レベルにおける前進は不可能です。従来の思想の批判・検討もできません。

恋知という発想=思想は、理論体系ではないですし、宗教性もありません。よき生の原理を踏まえて日々を生きること(実践)で、さまざまな領域でよきものを花咲かせる、という効果をもたらす態度です。知らぬ間に深く効きます。強い宗教(キリスト教や日本の天皇教など)や強固なイデオロギー(マルクス主義など)を必要としない自由でしなやかな生を可能とする原理、それが『恋知』です。

それは、紀元前5世紀に誕生したソクラテス(アテネ)とブッダ(ネパール・インド)、それに続く老子(中国)、また、中世の親鸞(日本)や20世紀のサルトル(フランス)らの実存思想とも重なる人間性を豊かに開花させる思想です。

孫のなな&れんの運動会で。

おんぶしているには、

わたしの知らない女の子(笑)。

2018年10月6日(66歳)武田康弘